As a teenager obsessed with Tori Amos, I listened to each new release in what now seems like an old-fashioned way: as an album, considering how each song led into the one that followed, considering the emotional and narrative arcs from start to finish. However, like an obsessed teenager, I also wanted to stitch each album together, along with each song, to see a thread between Boys for Pele which ends with “Twinkle,” and From the Choirgirl Hotel, which begins with “Spark.” In other words, I already thought like a poet arranging a manuscript.

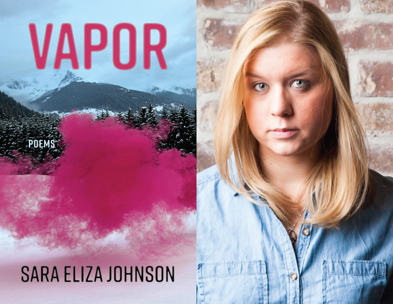

So, it was with much anticipation that I encountered Sara Eliza Johnson’s second collection, Vapor, as I adored her debut, Bone Map, and was deeply curious about where her work would take her. Much of what I loved about Bone Map is present in Vapor; in both there’s a strong sense of world-building—or in the case of Vapor worlds-building—though these worlds are built, in both collections, with spare materials. Both are informed by trauma, grief and loss, but I feel a strange, at once tenacious and hesitant resilience in Vapor, whose speaker is migratory, is transitioning/evolving—into what or whom, we can’t be sure.

Like Bone Map, Vapor has a muted palette; it is drenched in shadow though also sparked with honey, with radioactivity. In Vapor, we follow a speaker whose curiosity about her own wounds and perception of self as unlovable is balanced by—perhaps challenged by—a curiosity about the worlds beyond—about what it might mean to visit Titan or Proxima Centauri or the radioactive landscapes of a future earth. The speaker seems so deeply uncomfortable with having a/experiencing a/being a self that the only way to make amends with this alienation within oneself is to look without—to become an alien, a mutant, a revelation.

While Johnson deftly balances narrative and lyric impulses, I found myself most drawn to the poems with more of a narrative arc, such as “Pyroclast,” which comes early in the book. In it, the speaker gives birth to her own pain, “a newborn foal / I nursed on my own milk / and licked dry after rain.” Though she feeds it what she can, it wants to “climb back / inside” and “exhausted, I let it come / home. A heart can beat // outside a body. So can a wound.” Here Johnson’s ability to write with restraint and tenderness about pain, grounding it through such haunting imagery, is showcased. What I most admire here, as in other poems, is the ways in which the interior landscape and exterior landscape are, if not quite twinned, somehow made siblings. The poems seem as much to mourn and wrestle with interpersonal trauma as they do ecological trauma, and yet avoid making false equivalencies. Indeed, there’s a way in which the poems argue that personal healing or transformation might be the gateway to ecological healing. Or, the poems seem to say with a shrug, if not, departure from the self, from the earth, might be best.

Thus, there’s a speculative quality to Vapor, as the poems interrogate off-planet landscapes. I especially appreciated, the “Titan” sequence, three poems that explore the lakes of Titan, one of Saturn’s moons. In “Titan (Kraken Mare),” one of the questions Vapor raises is centered: what is consciousness and how might it migrate or evolve to inhabit the universe? The poem uses the second person to explore what this might be like:

Now you open. Your new eyes in this lake—

or not your eyes but a memory

of sight—as like blood vessels the waves open in you—

[…]

—you the brightest mote in the eye of the lake

that opens for you, lets you

grow your mind deeper within it, and which through you learns the miracle

of mitosis: a kind of breathing through dream.

Here, again, we see the blending of the interior and exterior landscapes—the waves become blood vessels the “you” pours itself into—as well as a sense of hope in this alien world: the word “open” repeats five times across the body of the poem, as it moves from harsh openings, such as “a wind had once disemboweled you, hollowed out your face” to the image of “grow[ing] your mind deeper within it,” suggesting a homecoming, a renewal, even mutation. Even the use of the second person, which is frequent in Vapor suggests otherness—this is happening to someone else, or some part of the speaker that feels apart from herself.

This distancing ebbs and flows within the collection and I find myself most drawn to those moments when the speaker’s vulnerability, so often obscured by sharp imagery and observation, shines, as in “Mutant,” (originally published in Southern Indiana Review) which comes near the collection’s end. The poem begins, “All the wildflowers turn away from me / as I pull my shame up from my throat.” The shame is an organ and a wild creature, “a black jellyfish, a tentacled heart still / connected to me by a single blue vein.” And then—one of the many startling revelations the collection offers: “I know everything needs love, even this creature / which opens, despite its pain.” This compassion for the self, for the self’s experience of shame allows the speaker to, at last, also access her power; the poem ends:

I am an irradiated thing that needs someone

to hold it closed, and no one can hold a thing

like that long enough to love it

unless maybe they, too, have been ruined,

cast out or kept hidden,

named abomination

after someone tried to bury their power

and failed.

Here the slippery diction of “hold it closed” rather than “hold close” is telling: the speaker is not asking to be held as a lover might, but rather as an overstuffed suitcase that requires pressure to be zipped. That is, perhaps, that pain recognizes pain; trauma recognizes trauma; and while each pain, each trauma, is individual, if we are all part of a ruined ecology, if we are all part of a singular yet complex consciousness, might recognition serve as a bridge? Might we be able to tell a wound it’s okay to heal, to close? Might our buried power irradiate us and change us into something, dangerous yes, but renewed?

Such wonderful questions—and that, to me, is what makes Vapor an excellent book. I am left with so many questions. I am not sure of the answers, but I know they require curiosity, bravery, a willingness to migrate, to transform into something that may contain the human but seeps beyond it.

<

|

Sara Eliza Johnson received her MFA in poetry from the University of Oregon and her PhD in creative writing from the University of Utah. Her first book, Bone Map, won the 2013 National Poetry Series, and her second, Vapor, was published by Milkweed Editions in 2022. |

|

Amie Whittemore is the author of the poetry collection Glass Harvest (Autumn House Press), Star-Tent: A Triptych (Tolsun Books, 2023), and Nest of Matches (Autumn House Press, 2024). She was the 2020-2021 Poet Laureate of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and was named a 2020 Academy of American Poets Poet Laureate Fellow. |