Plating the Poem, Reclaiming the Story: A Conversation with Erin Elizabeth Smith

by Amie Whittemore

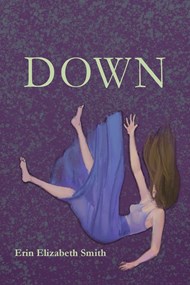

Amie Whittemore: I really enjoyed your latest collection, Down (Stephen F. Austin State University Press, 2020), and its close engagement with place, body, and memory: how where we are shapes how we see ourselves and our pasts, and how all of these can become strange—like Oz or Wonderland, both places you reference throughout the collection—through the effects of grief, trauma, and reckoning. I have questions about all these themes, but let’s begin with place, as scene-setting is a critical component of the first section of the book. In “Mapmaking,” the speaker states,

I am everywhere today—

the red and purple living room

where I burrowed in the blankets of a man

I used to love. A candy cane

rocket parked on Carolina fairground.

The orange trill of space heaters

on a Hattiesburg bar.

So, two questions: 1) how would you characterize the relationship between place and memory in Down and 2) as a writer, how does place influence your writing practice?

Erin Elizabeth Smith: When this book started to come into being, I had recently moved for the twenty-ninth time in twenty-eight years; this move was from Mississippi to Tennessee, which was also the ninth state that I’ve lived in. So much of the way that I think about memory is tied to the place—a childhood in the South, coming of age in the Northeast, grad school in the Midwest and Gulf Coast. To think of personal change is, for me, to think of where that change took place, but to think of love is also the same. So many of the relationships I had in my twenties were so deeply tied to where I lived that the place itself feels rooted to their loss. Maybe this is why I wasn’t able to write about Tennessee until my husband left it, until it was a place of grief and, eventually, healing.

When I move to a new place, I find myself ravenous for its histories, its idiosyncrasies, its notes that make it uniquely itself. In moving to Knoxville, most of the people I met in my first year were also transplants, so it took a while to truly understand the ins and outs of this Appalachian city that is not the South that I understood. This unearthing and discovery, though, is part of what makes the writing process so much richer; the way we surprise ourselves in our own education.

AW: I love that idea of “unearthing and discovery,” and how coming to know a place is often a journey of coming to know one’s self—through, as you note, grief and healing, which brings us to another dominant theme in Down, the exploration of a marriage coming to an end. This returned me to Jack Gilbert’s “Falling and Flying,” and how that poem refuses to position a marriage ending as failure, rather simply “coming to the end of [its] triumph.” I’d love to hear how you see the marriage in Down in relation to Gilbert’s logic. As a touchstone, poems such as “On the Third Month of Separation” and “Alice Re-Watches Garden State” come to mind: “On the Third…” ends “in this world, nothing / is finished or untoothed,” and the latter poem begins “What I know about moving on is nothing / like how it really works.” So maybe the question is: do marriages ever end?

EES: Before I was married, I thought that a divorce was just an expensive break-up. That it would carry the weight that the end of previous long-term relationships had. Even though I was married for less than a year, the weight of divorce cut much deeper than expected. Maybe it’s the promises? Maybe it’s a letting down of the guard in some way? I’m still unsure and exploring, but the way it brought me low was something I was in no way prepared for. I kept looking at other people’s stories of divorce that worked as buoys on the long bay, ways of getting from one thing to the next.

While I think the end of most relationships haunt in some capacity, the navigation of a divorce carries with it a different kind of weight, which can keep resurfacing in strange ways. My marriage’s end was neither a failure nor was its original existence a triumph. Our romantic relationships are not what define who we are in the world. Instead, it is the ways in which we grieve, heal, and grow.

AW: I love that perspective on the role of grief, healing, and growth and how they ground the individual, in ways similar to geography. Which brings us back to place! In section two, “A Fabulous Beast,” the issue of place, particularly home place, becomes further complicated with more exploration of real (Illinois, West Virginia, Delaware) and invented (Wonderland, Oz) geographies. These landscapes come into conversation with each other through the perspective of Alice, mainly, though she also enters into conversation with Dorothy. In “If Alice Lived Here,” the speaker notes “maybe home is a made-up place— / like love, like Wonderland.” How did you arrive at Alice and Dorothy becoming central figures in the collection?

EES: The first semester after my husband left, I was teaching a course focused on the literature on which Disney films were based. In preparation for the course, I watched every version of Alice I could find (there were quite a few that had just come out) and read a ton of the history of the books including the biography of Alice Liddell, the inspiration for Carroll’s Alice. Thus, the character was on the brain.

But it was in my reread of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland that I realized how this novel was different from the tales that followed. Alice wasn’t trying to get home. She wasn’t trying to defeat an evil monarch or find adventure, buried treasure, or even herself. She moved from place to place because she had to. For me, the story was about momentum, how you get through the strangeness of a new world without purpose, without goals. You move because you have to, and there was a beauty in that that rang true for that moment in my own life.

It felt important to put Alice in conversation with Dorothy, whose character and original story is based heavily off of the Alice books, partially to showcase their differences. To highlight why home isn’t something that one needs to find outside of the self.

AW: I love this perspective on the self as a kind of home and also appreciate how Alice and Dorothy’s experiences as literary characters are used as critiques of the male gaze and the male imagination: “I’m moved / ball-headed, from one adaptation / to the next,” Alice notes in “Neco z Alenky,” “all by men who want / to make me nubile, blonde, / each in wonder of their new version / of my world.”

The biographical speaker feels this pressure too, to see herself through the lens of the men in her life, particularly her ex-husband: “how you found me / like I look for men now, as hurt / and as clutching as you” (from “Dear John”). How do Alice’s—and to a lesser extent, Dorothy’s—experiences refract the more biographical speaker’s perspective on these issues?

EES: One of the things that I thought about a lot was the ways in which seven-year-old Alice Liddell helped to narrate the original version of the tale that Charles Dodgson (AKA Lewis Carroll) created and how her influence is never given credit in the story’s creation. Part of the genius and weirdness in this collection is based in child logic, which Dodgson, in some ways, steals from her. Think about the ways in which Alice functions—it’s not the story of a girl trying to get home (this trope comes more from the Oz books which later abandon it in favor of a more speculative world), but rather a girl who explores for the sake of exploring. Who moves to the next thing as if in a dream, with no purpose, no plan.

This is the story of many important girl characters, characters that shape us deeply as young readers. These characters as the pawns of male authors seemed important in the ways in which I thought about my own life and how so many of the choices I’ve made have been driven by men in my life. In many ways, this book is about reclaiming my own story.

AW: Not only are these poems imaginative, heartfelt, and smart—and, as you suggest above, actively feminist—they are also delicious: appetite, and the objects of appetite, feature prominently throughout the collection, though particularly in the latter half. The third section, “The Moon, and Memory, and Muchness,” opens with “Alice in Louisiana,” its speaker wondering how “anything survives this appetite / for all things sumptuous.” Later, in “Gastronomy,” the speaker states: “we eat and we become / something hungry….Nothing left of us but the urge / to consume something miraculous.” There’s a sense in these poems, as well as in others, that appetite defines the self; not only are we what we eat, we are what we want to eat.

I also know you’re a wonderful cook. So, I’m curious about the connections you see between cooking and writing: how does your experience in one mode shape your experience in the other? Or, to lean into the pun, how do these two practices feed each other?

EES: Certainly, both ideas here are about appetite, not just what we want to eat, but what we want. There’s a reason that the language of sex and food have been conflated since there’s been language, and it’s hard for me to write about desire without thinking about the sensual in terms of all of the senses.

Because cooking is not just an art but an obsession for me—I read cookbooks for fun and don’t even know what a “simple” meal is anymore—the language of cooking becomes part of the language that’s used in my writing in the same way any obsession can. But on the other side of things, I do feel that the way I think about poetry also bleeds into my cooking—the use of negative space in plating, the editing of ingredients, the ways in which you can blend form. I think all artists find their art in other places as well, the ways in which things seem to seep into one another. But with food, it’s something you have to engage with in some way to survive. Why not make that engagement as pleasurable as possible?

AW: Agreed! I also think there’s something to be said for reclaiming, not only one’s story, as you noted above, but also one’s appetite, one’s desire for and experience of pleasure. I relish that the title of the last section is “Everything’s got a Moral (If only you can find it)” and how it explicitly confronts the desire/expectation of a lesson to come from loss and grief; that it both invites and questions whether and how we learn from experience.

I feel there is often pressure in poetry collections to mimic some of the conventional actions of a novel—to have a plot for instance, or at least some narrative tension, especially if the poems are individually bent toward narrative. And, while your poems are grounded in narrative, they also are lyrical, meditating on the texture of memory, on those moments where “the last snow pants in the milky dawn, / unable to stay anywhere but afloat” (“The Last Snow”). As a poet, how do you balance your interest in narrative propulsion with the desire to stay “afloat”?

EES: As an editor, I spend a lot of time thinking about the story that a book tells as well as figuring out the best way to tell it. While I appreciate a certain chronology in a collection, I think it’s important to also remember that we don’t live out our lives in that same chronological order; memory, repetition, routine, even kinds of forgetting, are all ways in which we circle around and around in a way that cannot make a straight line.

I think poetry collections are so aptly able to do this work through the ways in which we call back and call forward to ideas that are important in the lives of what we create. I certainly didn’t write these poems in the same chronology they appear in the book; some weren’t even Alice poems, but instead reworked to fit within the framing of the conceit, which further illustrates the ways in which we come back to the same ideas, losses, and obsessions again and again.

AW: Finally, I’d like to zoom out a bit from Down and talk about your creative practice more generally. Anyone who knows you, or at least knows your presence in the literary community, knows that you are extremely active in supporting other writers through your nonprofits, Sundress Academy for the Arts and Sundress Publications, and the many projects that live under these sunny umbrellas. You are also an award-winning teacher at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville. How do you protect time for your own work in the midst of your many responsibilities?

EES: Honestly, this took a lot of time to figure out. Most of this book was written in my first few years in Tennessee, but by the time the majority of the poems were on the page, I was creating the residency program here in Knoxville, and I didn’t touch the manuscript, or my own poetry at all, for almost two years while I focused my life towards making sure that the farmhouse and the projects we were fomenting here in Knoxville were able to stand on their own.

I realized after we had opened the farm for short-term residencies and filling those spots, that I needed to figure out a way back to my own writing. This started with the workshop and retreat series that we run here at SAFTA, writing poems alongside the workshop participants and working towards a new collection. Eventually the SAFTA crew and other local writers started doing what we call Poetry Crossfit, where we give each other a certain set of rules and thirty minutes to write a poem. We come back. Share. Then rinse and repeat. It’s what I like to refer to as “making clay,” i.e. getting something down on the page that you can work and rework later.

This has been my primary way of writing for the past five years simply because I do not have the time to sit around and wait for “the muse,” or I’m alone in the forest gathering mushrooms, or standing above a pot poaching an egg, or at the white board talking about the importance of understanding audience, when inspiration strikes, and there’s no place or time to write those sudden thoughts down. It’s okay, though, because sometimes the language that you have in that minute isn’t what’s important. It’s knowing that when you do need the words to come, they will.

Erin Elizabeth Smith is the Executive Director for Sundress Publications and the Sundress Academy for the Arts. She is the author of three full-length collections of poetry, most recently DOWN (SFASU 2020), and her work has appeared in Guernica, Ecotone, Crab Orchard, and Mid-American, among others. Smith is a Distinguished Lecturer in the English Department at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville.

Amie Whittemore is the author of the poetry collection Glass Harvest (Autumn House Press). Her poems have won multiple awards, including a Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Prize, and her poems and prose have appeared in The Gettysburg Review, Nashville Review, Smartish Pace, Pleiades, and elsewhere. She teaches English at Middle Tennessee State University.