State of the U

by President Ronald S. Rochon

State of The U - Otherness

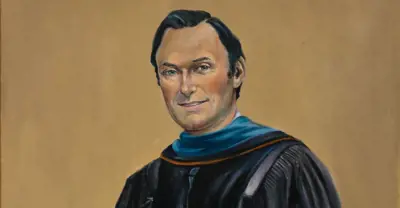

A few months ago, my official presidential portrait was revealed and hangs in perpetuity in the David L. Rice Library alongside those of the preceding three USI presidents. Seeing it stirs up memories of my path to reach this point in my life and career, a journey I have walked as a direct result of standing on the shoulders of my ancestors. Seeing it also reminds me of another image of myself, one captured when I was a young man traveling outside of the United States for the first time.

It was the summer of 1983, and I had just earned my bachelor's degree from Tuskegee University. I had hoped for a car as a graduation gift, but my mother decided a trip to Northern Africa, in the company of my Aunt Carol, would be more valuable to my future.

Instead of driving a new car, I found myself moving through foreign lands for the first time in my life, surrounded by Brown-skinned people who outwardly looked like me but were different in many ways. They spoke a language I could not understand; they followed a multitude of faiths and religions that differed from my Christian upbringing; they consumed foods I had never eaten; they engaged in sports and games I had never played.

As I wandered through Cairo, Egypt's marketplace in my free time, I worked hard to engage with the people—most of whom spoke some English to my nonexistent Arabic—selling spices, dried fruits, nuts, trinkets and other items of interest to local shoppers and tourists like me. At one stall, I was encouraged by the vendor to try on and purchase a gallabīyah, the traditional flowing garment worn by males in arid lands, and at another booth I tried on a ghutra, the headdress worn by some men in the region. In donning the garments, my intent was not to appropriate another's culture but to appreciate it, as I had come to learn by engaging with people on the journey, that dressing in a nation's native clothes was viewed as a sign of respect.

Commemorating my brief experience dressed in these traditional garments—dressed as someone other than who I was—and documenting my time in Egypt is a photo of me grinning. At 23, I was a skinny young man with big hair, facing an untapped future filled with possibilities. As someone on the cusp of his tomorrow, I had a sense of myself and where I was going and what I could achieve if I worked hard. But I did not understand what assumptions others could make of me.

To the border guards at the airport upon departure, my Brown skin labeled me Egyptian. That label alongside my U.S. passport created an assumption that I was attempting to leave the country under false pretenses. My passport was scrutinized for signs of forgery. My documents were checked, double checked and triple checked. My palms sweated. I grew anxious as I watched others proceed through customs. I was eventually allowed to board the plane and come home, but the situation could have been worse, and it often is when people make assumptions of others.

In recent years, we have witnessed a rise of violence in Indiana based on the assumptions of others and what they represent; violence directed at people because they looked different. A 19-year-old man attacked a Muslim woman in a café, choking her in front of her husband and 9-year-old daughter as he attempted to remove the hajib covering her head. Later, he claimed to be drunk and not the type to ever hurt anyone. Yet he did. More recently a 56-year-old woman stabbed an 18-year-old Asian college student on a city bus. Her justification? "One less person to blow up our country."

Assuming the worst of others based on indirect and incorrect teachings, judging them on preconceived ideas resulting from the color of their skin, their gender, the way they dress, wear their hair, their religion practiced, their sexual orientation, or gender identity is the foundation for destruction. When we fail to see the potential in others—especially children and young people—when we fail to see their humaneness, when we fail to see and honor the light in them, the same light that is within us, we fail as a society. We fail ourselves.

As we listen to our own thoughts and assumptions, what do we hear and see? Do our perceptions lead us to assume the best or worst of others?

All of us arrive where we are through varying degrees of hard work, tears, toil, oppression, discrimination, struggle, liberatory thought and behavior, resiliency, perseverance, collaboration, prayer and love. All of us deserve to be recognized for who we are and not what someone assumes of us. Democracy makes that possible. But democracy does not come unchallenged.

Exposure to people different from us—whether they are from Chicago or Luxor—is powerful and life altering. When we look at someone who at first glance appears unlike ourselves, take a moment to peer deeper and discover how alike we all are. All humans possess dreams and aspirations, from the underserved to the most powerful.

It takes work to see past the façade of someone to find their true essence, to find the light in them, the same light that is in all of us, as opposed to immediate disdain and assumptions that they are the "other" and therefore pose a danger.

I wonder if anyone looking at the image of me in the gallabīyah and ghutra (other than those who loved me) could have foreseen I would one day become a university president. Would they have taken the time to look beyond the color of my skin and the clothes I wore to understand my potential or merely taken in the trappings that said "other?"

Every moment in time is part of our larger life journey. Every moment in time offers each of us the opportunity to grow and change through self-awareness. Every moment in time offers each of us the opportunity to make a positive impact on society. Every moment in time offers each of us the opportunity to teach our children to be better, to do better. Every moment in time offers each of us the opportunity for self-discovery. Every moment in time offers each of us the opportunity to celebrate humanity. To celebrate the other.

President Ronald S. Rochon