College of Liberal Arts Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Committee

Statement Condemning Racism and Police Brutality

July 2020

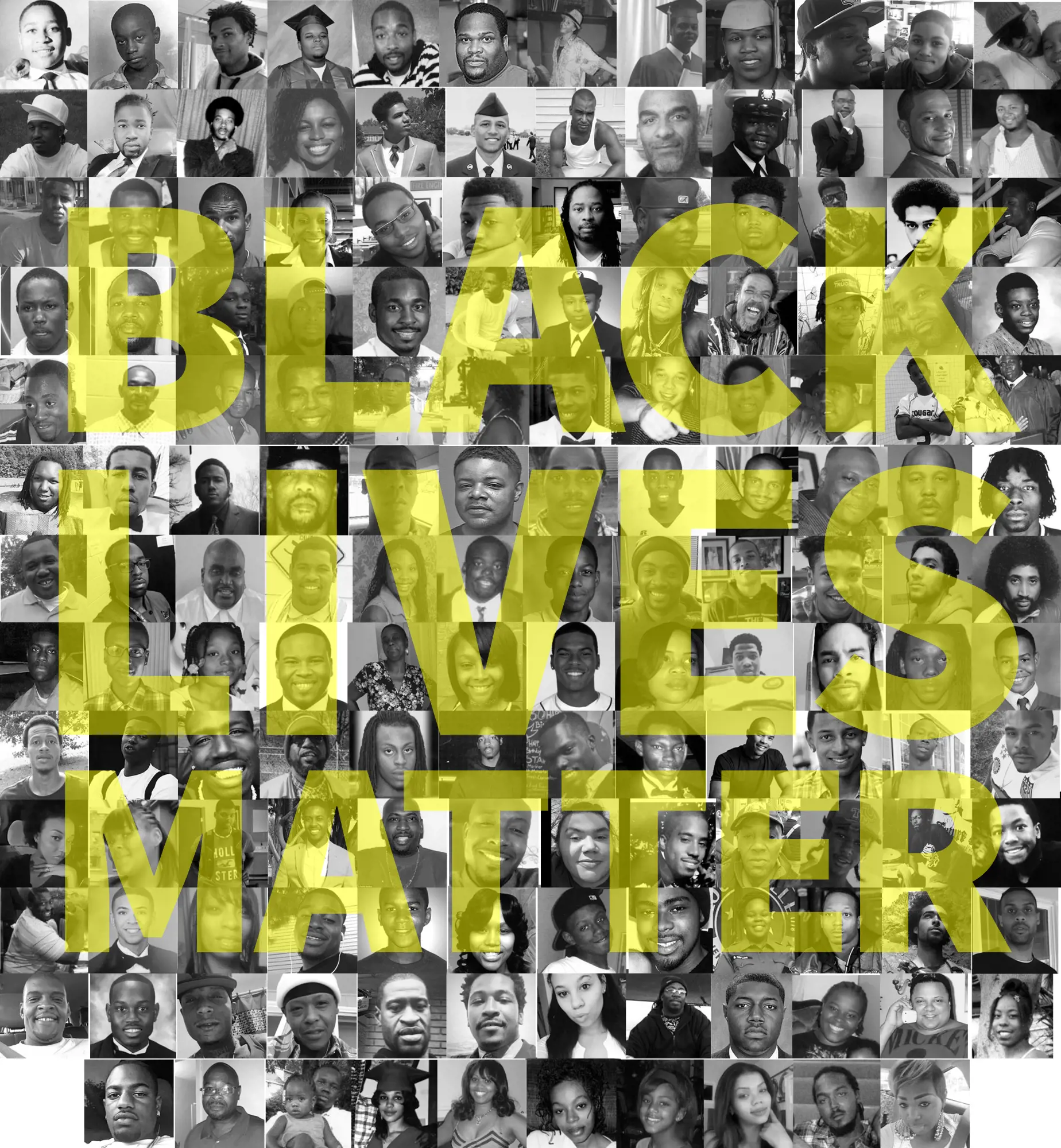

George Floyd. Ahmaud Arbery. Emmett Till. Paterson Brown. Laquan McDonald. Aiyana Stanley-Jones. Korryn Gaines. Rayshard Brooks. Tony McDade. Shelley Frey.

The College of Liberal Arts Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Committee (LA EDIC) stands in support of the Black Lives Matter and Say Her Name movements. It is important we say the names of those we have lost to racism and police brutality. We hold zero tolerance for white supremacy, racism, and discrimination of any kind. A strong liberal arts education is essential to dismantling systems of oppression, and USI’s College of Liberal Arts wishes to lead this charge for its students, faculty, staff, and the larger Evansville community. We believe young people are change bearers, and our students are key to creating a more equitable system where all can thrive.

The writer James Baldwin said to be Black and conscious in America was to live in a constant state of rage. Without a close look at history, it may be hard for many in the United States to understand this statement. The phrase “Black Lives Matter” has never suggested that only Black lives matter. It is a recognition that historically, and currently, there are structures in place that place less value on the lives of Black people. This is a stark reality that is easy to ignore if you are white; impossible if you are Black.[1] Indeed, without historical context, it is impossible to understand the intricacies of white privilege or how white supremacy is inseparable from our nation’s development.

The problem of policing is a long-standing problem of horrific proportions. Like all historic American institutions, we know the history of policing in America cannot be told without telling the history of white supremacy. The very first state-funded police forces were not created to serve and protect, but as slave patrols that scoured cities and countrysides looking for Black people to return to slavery, where they were subject to the cruel physical abuse and sexual depravity of their white masters.

After slavery, we saw the Jim Crow era, a hundred years of lynching, humiliation, and voter suppression across the United States. Along with the physical threats and violence, symbols of white supremacy were erected in the form of statues and the prevalence of the Confederate flag. These monuments were not a historic Civil War-era phenomenon, but rather the racist response to Black freedom struggles in the early twentieth century and during the Civil Rights era.

In the early 1960s, Gallup polls revealed an astounding level of white privilege which indicated that white Americans were oblivious to racial disparities. In the series of Gallup questions, respondents were asked whether Black people had “as good a chance” as white people to access education and if Blacks were treated fairly in their local communities. 85% of white people believed that Black Americans had the same opportunity in education as white Americans, and 69% of white people perceived that Blacks and whites were treated equally within their communities. This was at the height of segregation when Black schools were inferior, and Black people were daily humiliated, forced to sit at the back of buses, refused services at restaurants, and were not allowed to register to vote. Meanwhile, police across the country stood in the way of Black voting rights, harassed, arrested, and terrorized Civil Rights workers, and enforced segregation. Local law enforcement and the federal government worked together to demonize Black culture and organizations such as the Black Panther Party for Self Defense. This organization was established to protect Black neighborhoods from police brutality and created community aid programs such as free breakfast for school kids, ambulance services, health care services, and medical clinics. Currently, we see all manner of protest being denigrated, from kneeling to marching.

Breonna Taylor. Darnisha Harris. Layleen Polanco. Rekia Boyd. Pamela Turner. Jerame Reid. Philando Castile. Alton Sterling. Gregory Hill, Jr.

While it can be tempting to wave away these historical facts as things that happened “back then,” it is critically important to recognize the ways in which Black and Brown people in this country continue to struggle against oppressive systems. While there are no more white only signs, police and vigilantes acting as police restrict Black people from walking, jogging, playing, or just living. We also still see racial disparities across all areas of our lives.

The United States incarcerates a greater proportion of its citizens than any nation-state on earth – and by a wide margin (with about 5% of the world’s population, the U.S. boasts approximately 25% of the world’s incarcerated humans). This has occurred largely since the early 1980s, with the proportion of American prisoners increasing about 280% in 30 years (1980-2010). By the turn of the 21st century, Black men born in the 1960s were more likely to have gone to prison than to have completed college or military service.

Even though we are all supposed to be playing by the same rules, disparities abound in the implementation of those rules. For example, Black and white people use drugs at similar rates, but Black people are six times more likely to be arrested and subsequently prosecuted for drug use. In fact, if Black and Latinx people were incarcerated at the same rates as white people, prison populations would decline by nearly 40%.

Black people, who are 12% of the U.S. population, make up 37% of prison populations. Currently, one in three Black men will serve some amount of time in prison, while one in 17 white men will serve time. Black women are over twice as likely to be incarcerated than white women. Fully 13% of the Black adult male population have lost the right to vote due to their involvement in the criminal justice system. In the states with the most restrictive voting laws, 40% of Black men are likely to be permanently disenfranchised.

In the age of COVID-19, Black unemployment is at 16.7%, while white unemployment is at 14.2%. This is nothing new: historically, Black unemployment is higher than white unemployment. In February of this year, before the pandemic hit, white unemployment was at 3.1%, while Black unemployment was 5.8%.

Black trans and gender-nonconforming individuals face discrimination across all areas of life, from employment and policing to healthcare and housing. A third of Black trans and gender non-conforming people have less than $10,000 in yearly income, which is more than twice the rate for trans individuals from all races (15%) and eight times the general U.S. population (4%). Black trans individuals are also less likely to own homes and are often denied access to homeless shelters. When they do obtain access to shelters, they often experience harassment and physical or sexual assault.

Shantel Davis. Natasha McKenna. Kayla Moore. Tyisha Miller. Atatiana Jefferson. Ryan Twyman. Patrick Harmon. Michael Brown. Jamel Roberson. Anthony Lamar Smith.

These names and others reflect our failing as a society to support and protect our marginalized communities. The names we speak — and the names we don’t know — were those of our community members, sisters and brothers, lovers and friends, parents and children. They were people who deserved dignity and were granted none. LA EDIC members realize it is possible to lapse into an academic or theoretical discussion of these issues and thus miss the visceral immediacy of real human suffering. That is why it is important to remember the actual individuals that have been the victims of police brutality and racially-motivated citizen vigilantes. It is also important to stand in solidarity with their families and friends, who have lost someone dear to them.

As university faculty, LA EDIC members are keenly aware of the tremendous influence university students have had on affecting social change in modern society. From resisting totalitarian communist regimes in Hungary and Czechoslovakia, to protesting foreign wars, to supporting women’s movements, and many more… university students have stood at the vanguard of important social movements.

We cannot forget those who have stood against oppressive systems: Native Americans and their allies at Standing Rock, who fought to protect our environment, increasingly under threat due to climate change. Black trans women like Marsha Johnson who were instrumental in the Stonewall Riots, which paved the way for the LGBTQA movement. #MeToo movement founder Tarana Burke and the many trans and cisgender women from all backgrounds who have spoken out against sexual harassment and assault. Many of these movements are led by people from a variety of backgrounds who are the same age as our students or younger. Faculty should openly stand with students who fight for change on this campus and in our community.

Brandon Glenn. Tamir Rice. Quintonio LeGrier. Freddy Gray. Eric Garner. Tarika Wilson. Miriam Carey. Trayvon Martin. Kendra James.

In line with our goals as a college, LA EDIC creates opportunities for activism within our committee throughout the next school year and beyond. We believe we are witnessing a real moment of social change, not just a transitory media event. Our conscience and desire to be on the right side of history should guide our actions. With the acknowledgement that silence is complicity, our commitments are to:

- Acknowledge complicity in how white supremacy culture has manifested itself in our community, and work together to dismantle these systems. We stand with the Black community.

- Support efforts to reallocate a significant degree of public taxation towards addressing the causes of social problems (such as substance abuse treatment programs, community mental health centers, and initiatives to end homelessness) rather than feeding what seems like an insatiable appetite of the prison-industrial complex.

- Develop an understanding of and fight anti-Blackness and white supremacy through personal growth and collective action. This can be achieved in part by current and future efforts to host speakers from a variety of backgrounds, adding statements around diversity and inclusion in syllabi, and work with First Year Experience courses to introduce students to diversity and inclusion programming earlier in their college career.

- Actively support initiatives on and off campus that support our most vulnerable community members; this includes campaigns like student pushes to increase the number of gender-neutral restrooms and availability of mental health-related resources on campus, the Equal Justice Initiative Soil Collection Project, and the creation of LA EDIC Student Voices Council. We will also look to expand our collaborations with organizations like SURJ, SPARK Society, and the Formerly Incarcerated College Graduates Network, among others.

- Celebrate positive change in our communities, like the involvement of young people in movements for change in the surrounding Evansville community, the recent Supreme Court ruling in favor of DACA, and the recent Supreme Court ruling that discrimination based on gender identity or sexual orientation is illegal.

Current times ominously remind us of past eras and the words of Malcolm X who said, “If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there’s no progress. If you pull it all the way out that’s not progress. Progress is healing the wound that the blow made. And they haven’t even pulled the knife out, much less heal the wound. They won’t even admit the knife is there.” This statement is our effort to acknowledge the knife is there and start the healing process.

[1] For our reasoning on capitalizing Black, see the Columbia Journalism Review’s argument.

For more resources, please see the LA EDIC resources page.